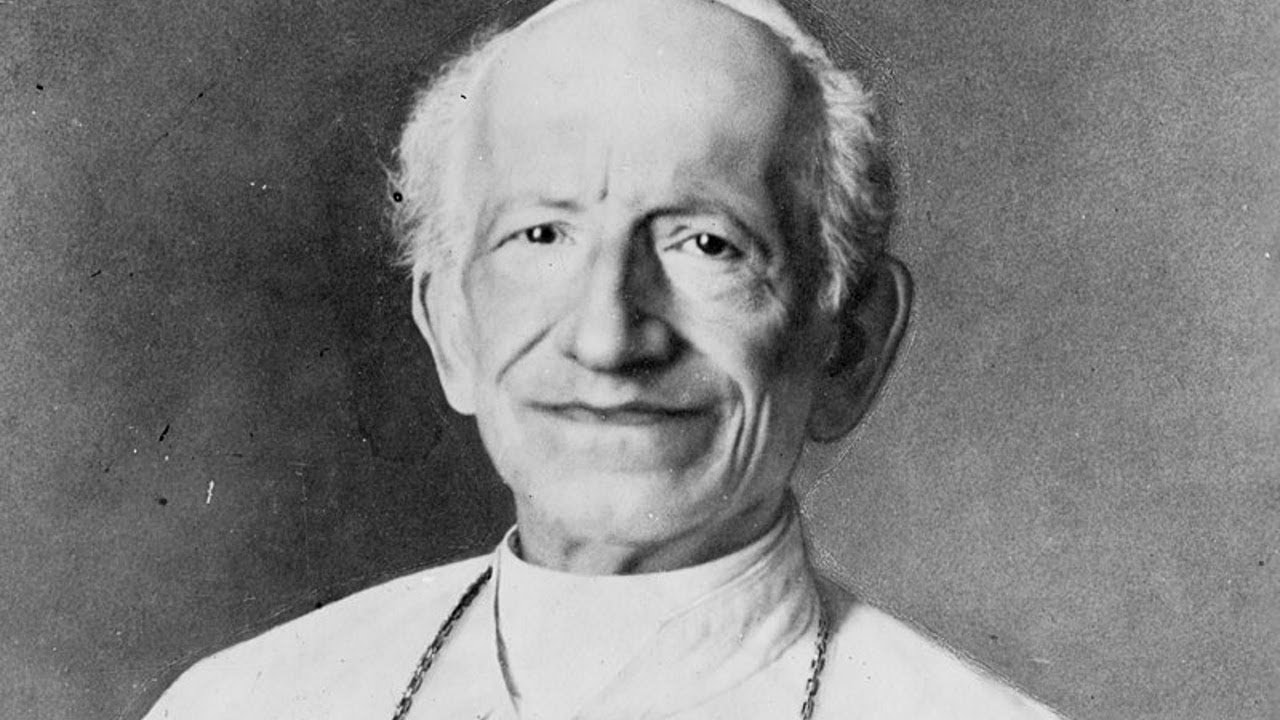

In Catholic Theology, a book published in 2017, Australian Theologian Tracey Rowland, a leading figure in contemporary Thomism and a member of the International Theological Commission since 2014, offers us a presentation of four essential Catholic approaches to doing theology which have determined the evolution and have been at the heart of the reflexive endeavour of the Catholic Church since, broadly speaking, the publication of Pope Leo XIII’s Encyclical, Aeterni Patris (1879).

The book is presented as an introduction to Catholic theology for students, and as a useful mapping of the major paths that theological reflection has taken since the end of the 19th century. But its remarkable richness of content also makes it a tool for all seasoned theologians who wish to refresh their knowledge of the history of contemporary Catholic thought. In going straight to the heart of the matter each time, the book allows us to understand the intellectual solidarities and oppositions that have shaped this history and that have influenced the course of events in the Church up to the time of the present pontificate.

Anyone who sets out to read T. Rowland's book is given a real introduction to theology, but it is an introduction of a specific kind. It is not a systematic exposition of the boundaries and foundations of theology, of the nature and purpose of the theological discipline, of its classical subdivisions, fundamental problems and methodological issues. Choosing a half-thematic half-historical approach structured around the major theoretical positions assumed by the great figures of theology on a certain number of essential problems, positions which together have given birth and consistency to the four theological currents analyzed, the author presents the fundamentals of each approach. We discover them not only in themselves, but as they have been defined in the course of theoretical confrontations, and according to the major epistemological and/or generational cleavages that have emerged, as ideological conflicts and profound cultural changes have brought new issues to the fore, thus inviting theologians to rethink the mission of the Church and their own role as intellectual leaders in Peter's bark.

After a brief presentation, in the first chapter, of the great principles and problems structuring Catholic theological thought from its origins (e.g. the Christian mystery cannot be reduced to a theological system; the unity of the theological vision must be maintained in spite of all the conceptual distinctions required by discursive thought; grace must be thought of in its articulation with nature; faith in its articulation with reason, etc.), we discover theology, chapter after chapter, through the concerns, commitments and battles of particular theological schools, thus familiarizing ourselves with the intellectual sensitivity of each one, the metaphysical references that each one draws upon, and the perspectives that they open on the future of Christianity.

Chapter II presents several types of contemporary thomistic approaches to theology ("Strict Observance Thomism" à la Garrigou-Lagrange, Gilson's existential Thomism, Rahner's transcendental Thomism, Lublin's Thomism (to which John Paul II is attached), Toulouse's Thomism, etc.). Chapter III recalls the battles fought by the great thinkers of the "Nouvelle Théologie" (de Lubac, Balthasar, Ratzinger), then the defence and illustration of their theses by and in the Communio journal, founded in 1972 (German and Italian editions). Chapter IV outlines the main reformist aims of the Critical Theology current, as it has been embodied since 1965 in the journal Concilium and in the theologically questionable works of Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx and Jean-Baptiste Metz. Chapter V describes the anti-hierarchical and subversive dynamics at work in Liberation Theology and concludes with an examination of the positions of Pope Francis, shaped by a particular type of Liberation Theology, People's Theology.

The work thus introduces us to the major positions of the major currents of Catholic theology, based on the major contributions of the major theological figures of Catholicism. Throughout the chapters, we see new theological sensitivities emerging, often in reaction to those that preceded them. Rowland's presentation also allows us to identify when and understand how we went from one theological era to another because of a particular paradigm shift. Moreover, she has highlighted the affinities, influences and filiations that have contributed to the rooting and perpetuation over time of these traditions of thought. In short, it is to a lived theology, which hides nothing of its existential significance, that Tracey Rowland skillfully presents us. The result is quite simply masterful. The Australian theologian deserves all our gratitude.

Clearly, Rowland's book is not for everybody. It is for people who have a real interest in theology, i.e. who like to grapple with tough theoretical questions like the place of philosophy in theology, the primacy of logos over ethos, the conflict between different branches of Thomism, etc. It is therefore obvious that one must have at least a basic knowledge of theology before trying to read Catholic Theology. The minimum would be to have read the Catechism of the Catholic Church and to be familiar with its content. And even then, one will face a real challenge in reading Rowland sometimes.

But even when one doesn't understand all at once, one learns a lot and draws a lot out of what the author exposes. Especially in terms of how to quickly identify theological positions and affiliations in books and speeches. Thanks to it, we learn about Garrigou-Lagrange or Rahner or Ratzinger or Bergoglio's main theological influences and stands. About the impact of theological currents on the life of the Church before and after Vatican II. About the confrontation between currents that are trying to "modernize" the Church, while others are more concerned with trying to keep a living connection with our Tradition, etc. It truly is an amazing book.

(Revised and updated on 08-24-2020 at 1:32 pm)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed