In previous articles, I’ve stressed the fact that, at the dawn of Greek philosophy, the main goal of Presocratics thinkers was to find rational causes to natural phenomena, and that, through a constant attempt to understanding and explaining nature, they were also confronted with two major problems: the question of God and the question of man. As time went by, these two other topics grew in importance. As we will see later, anthropology and ethics became central issues with Socrates. Then, Platon and Aristotle each played a key role in the acquisition of enduring metaphysical knowledge. The study of the physical world led to the study of the soul and of God.

Indeed, the search for an "archè", i.e. for a foundational principle explaining the cosmos, led Greek philosophers to define ever more clearly the nature of that underlying one cause of everything, which would be explicitly identified with God in Aristotle’ works (3rd century BC). Furthermore, the cosmological knowledge philosophers were trying to acquire couldn’t help but impact their understanding of man as a spiritual being, and of good human life as a way of properly interacting with the world as well as with other-worldly realities so as to achieve the philosophical ideal of wisdom, which alone allows human beings to live up to their spiritual vocation.

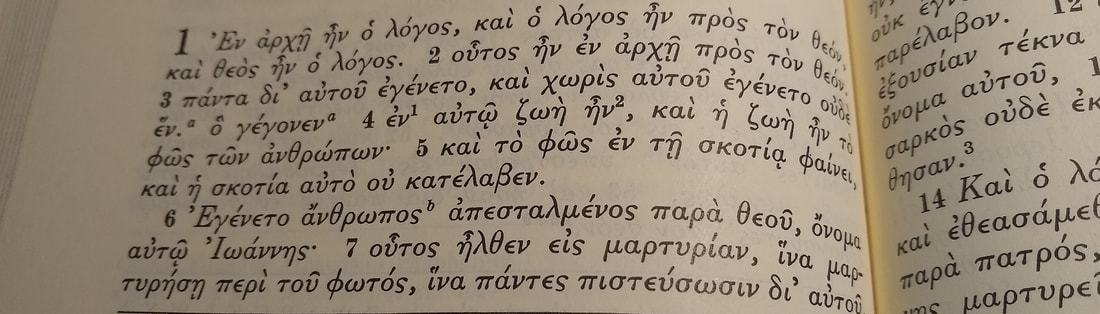

All this makes Greek philosophy very interesting in the eyes of Christians, who consider that the knowledge of God is the climatic experience we are meant to live in Heaven (“Now this is eternal life, that they should know you, the only true God” (Jn 17:3)); and who are themselves in search of a way of life attuned to the highest knowledge possible, a way of life worthy of the wisdom they were blessed to receive through God’s graceful revelation. The only difference between Greeks and Christians here, is that the knowledge Christians rely on is primarily revealed, and that their effort to live wisely depends on their good will for sure, but mostly on God’s grace.

What we ought to understand about what was said so far is this: the philosophical quest for theoretical knowledge was really just the first aspect of a broader and engaging endeavour, that of living wisely a good human life, a life lived in accordance with the highest knowledge possible about human nature, the cosmos, and its ultimate principle. Therefore, we shouldn’t see ancient philosophy merely as an intellectual endeavour aimed at knowledge. It was an existential commitment to the pursuit of wisdom, understood as a way of thinking, behaving and being all together. In sum, it was seen as a way of life. So just as Christianity can’t be reduced to a simple theological worldview, ancient philosophy can’t be studied as if it were only a theoretical “game”.

The similarity between the Christian religion and ancient Greek thought goes even further. We know that Christianity is calling for conversion, that is to say for an inner and outer transformation of man. So does ancient Greek philosophy, especially from the moment Socrates (c. 470 – 399 BC) appeared on the stage of History, and focused most of his discussions and debates with other philosophers, not on cosmological problems, but on anthropological ones. If Christianity is not merely a way of thinking, but a way of life, the same thing is true about philosophy. And, in both cases, the purpose of preaching and/or teaching is the same: to urge or enable conversion. Christianity offers a path of inner enlightenment and moral improvement that reshapes the whole self and reorient it toward truth, goodness and happiness. Ancient Greek philosophy claimed to do the same, in its own ascetical and contemplative way.

We are indebted to a French scholar named Pierre Hadot (1922-2010), for having rediscovered ancient philosophy for what it really was, namely, a school of spiritual and existential growth, rather than a purely “scientific” attempt to better know the world. This understanding of “philosophy as a way of life” and as an ongoing effort to comply with the basic philosophical and ethical rules implied by this way of life, is particularly adequate and relevant when studying the Hellenistic period (332 BC - 30 BC), where six philosophical schools, offering six different “ways of life”, were flourishing. They were all presenting themselves as fellowship, where a master/disciple relationship, friendship among its members, and the constant practice of spiritual exercises (understood as the shaping of mental discipline through reflection, imagination, and sensitivity) were all used as levers allowing the disciple to advance on the path of true lived wisdom.

Platonism, Aristotelism, Stoicism, Epicurism, Cynicism and Scepticism were promoting different ways of life, the aim of which was, no matter the theoretical, ascetical or ethical differences between each school, to reshape one’s worldview and one’s behaviour, so as to master one’s passions and live in accordance with the cosmic law (oftentimes assimilated to a divine principle) and fairly with all men. This renewed way of looking at ancient philosophy helps us to relate more easily to these men of the past, because, as Christians, we can spontaneously identify with their eagerness to become better men, through the understanding of a new vision of the world and the putting into practice of a new spiritual and moral behaviour, strengthened by spiritual exercises aimed at a profound and complete transformation of the self. These men were looking for the truth. They were also looking for justice and happiness. Just like us.

Indeed, the search for an "archè", i.e. for a foundational principle explaining the cosmos, led Greek philosophers to define ever more clearly the nature of that underlying one cause of everything, which would be explicitly identified with God in Aristotle’ works (3rd century BC). Furthermore, the cosmological knowledge philosophers were trying to acquire couldn’t help but impact their understanding of man as a spiritual being, and of good human life as a way of properly interacting with the world as well as with other-worldly realities so as to achieve the philosophical ideal of wisdom, which alone allows human beings to live up to their spiritual vocation.

All this makes Greek philosophy very interesting in the eyes of Christians, who consider that the knowledge of God is the climatic experience we are meant to live in Heaven (“Now this is eternal life, that they should know you, the only true God” (Jn 17:3)); and who are themselves in search of a way of life attuned to the highest knowledge possible, a way of life worthy of the wisdom they were blessed to receive through God’s graceful revelation. The only difference between Greeks and Christians here, is that the knowledge Christians rely on is primarily revealed, and that their effort to live wisely depends on their good will for sure, but mostly on God’s grace.

What we ought to understand about what was said so far is this: the philosophical quest for theoretical knowledge was really just the first aspect of a broader and engaging endeavour, that of living wisely a good human life, a life lived in accordance with the highest knowledge possible about human nature, the cosmos, and its ultimate principle. Therefore, we shouldn’t see ancient philosophy merely as an intellectual endeavour aimed at knowledge. It was an existential commitment to the pursuit of wisdom, understood as a way of thinking, behaving and being all together. In sum, it was seen as a way of life. So just as Christianity can’t be reduced to a simple theological worldview, ancient philosophy can’t be studied as if it were only a theoretical “game”.

The similarity between the Christian religion and ancient Greek thought goes even further. We know that Christianity is calling for conversion, that is to say for an inner and outer transformation of man. So does ancient Greek philosophy, especially from the moment Socrates (c. 470 – 399 BC) appeared on the stage of History, and focused most of his discussions and debates with other philosophers, not on cosmological problems, but on anthropological ones. If Christianity is not merely a way of thinking, but a way of life, the same thing is true about philosophy. And, in both cases, the purpose of preaching and/or teaching is the same: to urge or enable conversion. Christianity offers a path of inner enlightenment and moral improvement that reshapes the whole self and reorient it toward truth, goodness and happiness. Ancient Greek philosophy claimed to do the same, in its own ascetical and contemplative way.

We are indebted to a French scholar named Pierre Hadot (1922-2010), for having rediscovered ancient philosophy for what it really was, namely, a school of spiritual and existential growth, rather than a purely “scientific” attempt to better know the world. This understanding of “philosophy as a way of life” and as an ongoing effort to comply with the basic philosophical and ethical rules implied by this way of life, is particularly adequate and relevant when studying the Hellenistic period (332 BC - 30 BC), where six philosophical schools, offering six different “ways of life”, were flourishing. They were all presenting themselves as fellowship, where a master/disciple relationship, friendship among its members, and the constant practice of spiritual exercises (understood as the shaping of mental discipline through reflection, imagination, and sensitivity) were all used as levers allowing the disciple to advance on the path of true lived wisdom.

Platonism, Aristotelism, Stoicism, Epicurism, Cynicism and Scepticism were promoting different ways of life, the aim of which was, no matter the theoretical, ascetical or ethical differences between each school, to reshape one’s worldview and one’s behaviour, so as to master one’s passions and live in accordance with the cosmic law (oftentimes assimilated to a divine principle) and fairly with all men. This renewed way of looking at ancient philosophy helps us to relate more easily to these men of the past, because, as Christians, we can spontaneously identify with their eagerness to become better men, through the understanding of a new vision of the world and the putting into practice of a new spiritual and moral behaviour, strengthened by spiritual exercises aimed at a profound and complete transformation of the self. These men were looking for the truth. They were also looking for justice and happiness. Just like us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed